|

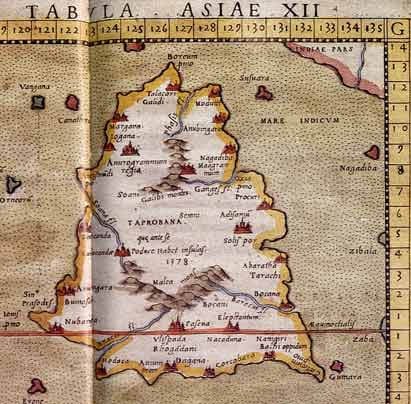

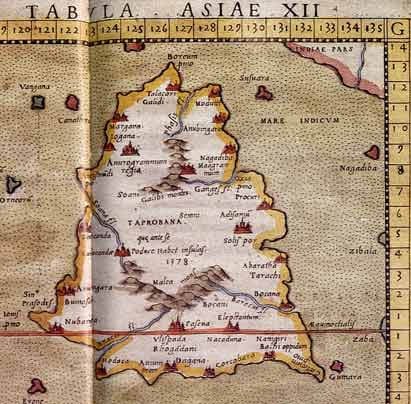

Historical

Map of Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka's first settlers were the nomadic Veddahs. Legend

relates them to the Yakkhas, demons conquered by the Sinhalese

around the 5th or 6th century BC. A number of Sinhalese kingdoms,

including Anuradhapura in the north, took root across the

island during the 4th century BC. Buddhism was introduced

by Mahinda, son of the Indian Mauryan emperor Ashoka, in the

3rd century BC, and it quickly became the established religion

and the focus of a strong nationalism. Anuradhapura was not

impregnable. Repeated invasions from southern India over the

next 1000 years left Sri Lanka in an ongoing state of dynastic

power struggles.

The Portuguese arrived in Colombo in 1505 and gained a monopoly

on the invaluable spice trade. By 1597, the colonizers had

taken formal control of the island. However, they failed to

dislodge the powerful Sinhalese kingdom in Kandy which, in

1658, enlisted Dutch help to expel the Portuguese. The Dutch

were more interested in trade and profits than religion or

land, and only half-heartedly resisted when the British arrived

in 1796. The Brits wore down Kandy's sovereignty and in 1815

became the first European power to rule the entire island.

Coffee, tea, cinnamon and coconut plantations (worked by Tamil

laborers imported from southern India) sprang up and English

was introduced as the national language.

Then known as Ceylon in History, Sri Lanka finally achieved

full independence in 1948. The government adopted socialist

policies, but promoted Sinhalese interests, making Sinhalese

the national language and effectively reserving the best jobs

for the Sinhalese, partly to address the imbalance of power

between the majority Sinhalese and the English-speaking, Christian-educated

elite. It prompted the Tamil Hindu minority to press for greater

autonomy in the main Tamil areas in the north and east.

The country's ethnic and religious conflicts escalated as

competition for wealth and work intensified. When Bandaranaike

was assassinated in 1959 tryingto reconcile the two communities,

his widow, Sirimavo, became the world's first female prime

minister. She continued her husband's socialist policies,

but the economy went from bad to worse. A Maoist revolt in

1971 led to the death of thousands. One year later, the country

became a republic and made Sri Lanka its official name.

In 1972 the constitution formally made Buddhism the state's

primary religion, and Tamil places at university were reduced.

Subsequent civil unrest resulted in a state of emergency in

Tamil areas. Sinhalese security forces faced off against young

Tamils, who began the fight for an independent homeland. Junius

Richard Jayewardene was elected in 1977 and promoted Tamil

to the status of a 'national language' in Tamil areas. He

also granted Tamils greater local government control, but

violence escalated.

When Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) secessionists

massacred an army patrol in 1983, Sinhalese mobs went on a

two-day rampage, killing several thousand Tamils and burning

and looting property. This marked the point of no return.

Many Tamils moved north into Tamil-dominated areas, and Sinhalese

began to leave the Jaffna area. Tamil secessionists claimed

the northern third of the country and the eastern coast. They

were clearly in the majority in the north but proportionately

equal to the Sinhalese and Muslims in the east. Violence escalated

with both sides guilty of ethnic cleansing.

By 1985, there were 50,000 internal refugees, 100,000 Tamil

exiles in India, no tourism, slumping tea prices and dwindling

aid (because of human rights abuses). Government gains in

1987 led to Tamil unrest in India, prompting concerns of an

Indian invasion. The two governments agreed that the Sri Lankan

Army would retreat and an Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF)

would maintain order in the north and disarm the Tigers. The

agreement led to Sinhalese and Muslim riots in the south over

the government 'sell-out' and Indian 'occupation'. Sri Lanka

became a quagmire of inescapable violence.

A 1989 Sinhalese rebellion broke out in the south and the

Marxist JVP orchestrated a series of strikes and political

murders. The country was at a standstill. When the government's

talks with the JVP failed, it unleashed death squads that

killed JVP suspects and dumped their bodies in rivers. A three-year

reign of terror resulted in at least 30,000 deaths. The IPKF

withdrew in 1990. The Tigers had agreed to a ceasefire but

violence flared almost immediately when a breakaway Tamil

group unilaterally declared an independent homeland.

Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated by a Tamil suicide bomber in

1991 and Premadasa suffered the same fate in 1993. Chandrika

Bandaranaike Kumaratunga became prime minister in 1994, and

president in 1995, and for the second time her mother Sirimavo

Bandaranaike became prime minister.

Chandrika Kumaratunga won a second term in office in December

1999. Days before the vote, the president and People's Alliance

coalition leader was the target of a LTTE suicide bomb attack

in which she lost the sight in one eye. In December 2001,

Ranil Wickramasinghe, who lost the 1999 elections, became

prime minister when the United National Party swept parliamentary

elections. This could have led to deadlock between Parliament

and the executive in dealing with high inflation, high unemployment,

poor infrastructure and, of course, the 18-year-old civil

war, but unexpectedly promising peace talks with the LTTE

have facilitated cooperation in the political process.

Peace talks brokered by a Norwegian delegation inspired a

one-month cease-fire beginning 24 December 2001 (the first

in seven years), renewed in January 2002. With the lifting

of a seven-year-old embargo on LTTE-controlled territory,

it seems peace is not a pipe dream.

Historical Kings and Queens of Sri Lanka

|

.png?v1) Cake Shop

Cake Shop Top Sellers

Top Sellers Kapruka Cakes

Kapruka Cakes Javalounge Cakes

Javalounge Cakes Galadari Cakes

Galadari Cakes NH Collection Cakes

NH Collection Cakes Breadtalk Cakes

Breadtalk Cakes Hilton Cakes

Hilton Cakes Kingsbury Cakes

Kingsbury Cakes Cinnamon Cakes

Cinnamon Cakes Gerard Mendis Chocolatier Cakes

Gerard Mendis Chocolatier Cakes Waters Edge Cakes

Waters Edge Cakes Divine Cakes

Divine Cakes Shangrila Cakes

Shangrila Cakes Mahaweli Reach - Kandy

Mahaweli Reach - Kandy McLarens Topaz - Kandy

McLarens Topaz - Kandy Sponge Cakes

Sponge Cakes Green Cabin Cakes

Green Cabin Cakes Courtyard By Marriott Cakes

Courtyard By Marriott Cakes Caravan Fresh Cakes

Caravan Fresh Cakes T Lounge By Dilmah Cakes

T Lounge By Dilmah Cakes Custom Printed Cakes

Custom Printed Cakes Customized Cakes

Customized Cakes Combo Gift Packs

Combo Gift Packs Chocolates

Chocolates Top Sellers

Top Sellers Kapruka Chocolates

Kapruka Chocolates Java Lounge

Java Lounge Ferrero Rocher

Ferrero Rocher Lindt

Lindt Sweetbuds

Sweetbuds Gerard Mendis Chocolatier

Gerard Mendis Chocolatier 5 Star Hotels

5 Star Hotels Cadbury

Cadbury Hersheys

Hersheys Kit Kat

Kit Kat Mars

Mars Ritzbury

Ritzbury Revello

Revello Kandos

Kandos toblerone

toblerone Other

Other Clothing

Clothing Sarees

Sarees Dresses

Dresses Ladies Tops

Ladies Tops T-shirts

T-shirts Lingeries

Lingeries Lungies / Sarongs

Lungies / Sarongs Jeans

Jeans Gents Wear

Gents Wear Kids Wear

Kids Wear Electronics

Electronics Home Appliances

Home Appliances Computers

Computers Personal Care

Personal Care Headphones

Headphones Tools/Machinery

Tools/Machinery TV/Audio

TV/Audio Laptops

Laptops Smart Watches

Smart Watches Cameras

Cameras Light And Power

Light And Power Mobile Accessories

Mobile Accessories Tabs

Tabs Gadgets

Gadgets Mobile Phones

Mobile Phones Drones

Drones Flower Shop

Flower Shop Royal Bloom

Royal Bloom Anniversary Flowers

Anniversary Flowers Birthday Flowers

Birthday Flowers Flower Bouquets

Flower Bouquets Chrysanthemums

Chrysanthemums Congratulations Flowers

Congratulations Flowers Custom Flowers

Custom Flowers Exotic Flowers

Exotic Flowers Getwell Flowers

Getwell Flowers Just

Just Lilly

Lilly Love And Romance

Love And Romance  Newborn Flowers

Newborn Flowers Pink Roses

Pink Roses Plants

Plants Red Rose

Red Rose Shirohana

Shirohana Sympathy

Sympathy Thank You

Thank You Wedding Flowers

Wedding Flowers Food / Restaurants

Food / Restaurants Fruit / Fruit Baskets

Fruit / Fruit Baskets Veg / Veg Baskets

Veg / Veg Baskets Gift Vouchers / Tickets

Gift Vouchers / Tickets Combo and Gift Sets

Combo and Gift Sets Grocery Items

Grocery Items Bagged Food

Bagged Food Beverages

Beverages Canned Food

Canned Food Cleansers

Cleansers Condiments

Condiments Confectionery And Biscuits

Confectionery And Biscuits Cut Vegetables

Cut Vegetables Dairy Products

Dairy Products Dessert

Dessert Eggs And Oil

Eggs And Oil Exotic Vegetables

Exotic Vegetables Flour / instant mixes

Flour / instant mixes Frozen Food

Frozen Food Global Food

Global Food Herbs

Herbs Juice / drinks

Juice / drinks Pasta And Noodles Categories

Pasta And Noodles Categories Pest Control

Pest Control Rice

Rice Seafood

Seafood Snacks And Sweets

Snacks And Sweets Specialty Foods

Specialty Foods Spices And Seasoning Categories

Spices And Seasoning Categories Bakery/Spreads/Cereals

Bakery/Spreads/Cereals Tobacco

Tobacco Vegetables

Vegetables Wellness

Wellness Greeting Cards / Party

Greeting Cards / Party Hampers

Hampers Jewelry / Watches

Jewelry / Watches Vogue

Vogue Swranamahal

Swranamahal Arthur Jewelry

Arthur Jewelry Stone N String

Stone N String Mallika Hemachandra

Mallika Hemachandra Raja Jewellers

Raja Jewellers Chamathka

Chamathka Tash Gem And Jewellery

Tash Gem And Jewellery Watches

Watches Mens Jewellery

Mens Jewellery Womens Jewellery

Womens Jewellery Kids Jewellery

Kids Jewellery Personalized Gifts

Personalized Gifts Customized Cakes

Customized Cakes Customized Drinkware

Customized Drinkware Customized Photo Albums And Frames

Customized Photo Albums And Frames Customized Message in Bottle

Customized Message in Bottle Customized Gift Sets

Customized Gift Sets Customized Clock

Customized Clock Customized Chocolate Box

Customized Chocolate Box Perfumes / Fragrances

Perfumes / Fragrances Hand Bags / Fashion / Shoes

Hand Bags / Fashion / Shoes HandBags

HandBags Ladies Shoes

Ladies Shoes Fashion Accessories

Fashion Accessories Wallets

Wallets Eyewear Accessories

Eyewear Accessories Umbrellas

Umbrellas Belts

Belts Fashion Gift Sets

Fashion Gift Sets Cosmetics

Cosmetics College Pride

College Pride School Supplies

School Supplies Books

Books Health and Wellness

Health and Wellness Vitamins And Supplements

Vitamins And Supplements Sexual Wellness

Sexual Wellness Ayurvedic

Ayurvedic Capsules

Capsules Soft Toys / Kids Toys

Soft Toys / Kids Toys Soft Toys

Soft Toys Kids Toys

Kids Toys Bicycles / Riders

Bicycles / Riders Baby Items

Baby Items Remote Cars

Remote Cars Diecast Model Cars

Diecast Model Cars Sports / Bicycles

Sports / Bicycles Mother & Baby

Mother & Baby Wine & Spirits

Wine & Spirits Home & Lifestyle

Home & Lifestyle Religious Items

Religious Items Automobile

Automobile Petcare

Petcare Intimate Essentials

Intimate Essentials Made In SL

Made In SL Kapruka Global Shop

Kapruka Global Shop See More Categories

See More Categories Get SL Merchandise

Get SL Merchandise Services

Services Reload Mobile Phones

Reload Mobile Phones Send Money/Vouchers

Send Money/Vouchers Realestate Services

Realestate Services Office Locations

Office Locations Get a Corporate Card

Get a Corporate Card Kapruka Careers

Kapruka Careers Contact Us

Contact Us Brands

Brands